Brancaster Chronicle No.57: Robin Greenwood Sculptures

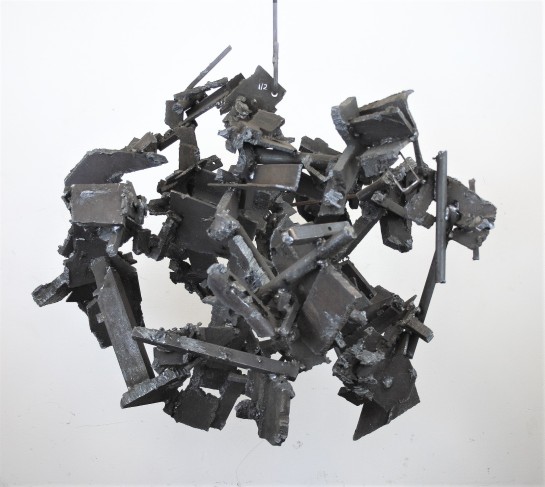

“Dérangement d’Estomac”, 2018, steel, 109x134x130cm

30th June 2018, London.

Taking part: Robin Greenwood, Sarah Greenwood, Anne Smart, Anthony Smart, Hilde Skilton, Mark Skilton, Noela James, Charley Greenwood, Alexandra Harley, John Pollard.

“Baroque Pastoral”, 2018, steel, H.100x102x104cm

“Dark Deeds”, 2018, steel, 101x117x107cm

“Ganix Weyn”, 2017-18, steel, wood, 68x123x97cm

“Jigger”, 2018, steel, 103x119x109cm

“Norse Laws”, 2018, steel, 96x110x110cm

“Orangetree”, 2018, steel, wood, stone, 84x97x84cm

“Sailor’s Trousers”, 2018, steel, stone, 97x109x92cm

“Shot Thro’”, 2018, steel, wood, plastic, 84x106x100cm

Watching this film of Robin’s sculptures, [ the second best way of seeing them as the photos tell me very little and do not aid identification] I made the note that not much challenges the three dimensionality of the sculptures and that chimed when Mark says his thing about ‘ too much ” three dimensionality.

The film does not change my original feeling that the large hanging piece “Derangement d’Estomac” 2018 and the one on the floor next to it “Jigger” 2018 are the best pieces and are very different to each other in the way they work.

I also noticed how few comments in the film described the space in the sculptures beyond space which surrounds the steel and makes it available to read through the work. The overall focus of the pieces is that of their physicality, hence my opening remarks when I rightly applauded the ‘stuff’ of them and the ‘feast’ in store.

So, back to my opening thoughts. I am suggesting that in other than the two sculptures I have separated out ,the amalgamation of so much stuff / content has perhaps left the space to being in a surrounding role, not active as part of the sense and in that of the ‘ structures’ Robin refers to.

The large hanging piece, as was pointed out in the dialogue, has a much greater range of steelwork and with that comes a more involved space in tension with a more open and flexible structure.

The smaller piece, in my memory, leaves much of the spatial ingenuity to the interplay between the solid and more packed grouping of the whole, up and down, side to side, played off against the bars of steel, feeling stretched and in tension across and through the structure.

Because of what I have said about how these two might work, I would suggest that they are abstract because the material and the space are both richly combined in non literal ways and become an intelligent whole beyond something I already know.

That particular ‘ feeling’ belongs to that piece alone . Will repeated viewings diminish that ? I hope not.

LikeLike

Very helpful/useful comment, Tony. Thanks. Lots of reasons—but one is it makes me feel less “guilty” about not really being able to identify the work in all the photographs. I’ve watched the film/video maybe 3 times now. Am beginning to get past the English accents, very SLOWLY beginning to make contact with the work.

There’s a nice Giacometti show up at the Guggenheim in New York now. I live in New York, have seen the show a number of times. Still it’s difficult really getting at the work. The Gugg’s a difficult museum for sculpture. They’ve got lots of work behind glass, lots of work only accessible from “the front.” No question I can see the Giacomettis a lot better than I can see Robin’s work. But it’s always a question: can you see what you’re looking at? Alex and Noella brought it up at the beginning of the Brancaster, John toward the end. It never really went away. It’s a good question. Both Robin and Giacometti are asking it even once you’ve gotten past the immediate physical difficulties of seeing the work in a particular location. Whose work is easier to see?

After listening to the Brancaster at breakfast this morning I took the question “Is Giacometti three-dimensional, too three-dimensional?” up to the Gugg. Does Giacometti ever open things up beyond believabilitly? Is there a “contradiction” in Giacometti’s work.

There are a couple of Brancusi shows up in New York now too—at the Gugg and at MoMA. The shows include photos and films as well as sculpture. How do Robin’s photos compare with Brancusi’s? Are Robin’s too “easy”/easily accessible somehow?

LikeLike

Jock says, ” are Robin’s sculptures too easy to see?”. Mark says, “are they too three dimensional?”

Jock reminds us of the homogenous surface of a Giacometti, a double whammy of wholeness, not only the ‘wholeness’ of the human body but the all overness of a non-particular surface.

Sometimes Robin’s work can be seen as an assemblage of parts, the parts being groups of smaller ‘things’, wholeness therefore being in the overall shape,form. Mark talked about ‘opening out’ and asked where Robin thought the particular piece he was looking at could go?

Is opening out an extension of language , an extension of content,complexity and variety certainly variety? Varying the condition of the material to affect the whole, the space, the welcome movement, to introduce ‘pause’ to change the ‘pace’,to create varying kinds of space to take on the dominating groups of over physical material, groups that you feel can be separated, bits taken out , without losing the whole.

Has Jock got a good point in hinting at the connection of ‘seeing’ with ‘..can you see what you are looking at?’

In putting these points together I sense the two best pieces of Robins, which I have already described ,have more relevant variety, more relevant everything

Mark’s bombshell of ‘opening out’ could, and certainly in my mind will, is going to “open out” this debate.

As an aside,and in an attempt to keep this going, we intend changing the running order and will follow this from Robin with the three other SCULPTURE films….so ..Mark then Tony then Alex.

LikeLike

We need to carefully distinguish Mark’s comments about the possibility of opening out sculpture, away from the ‘cluster’, which was speculative and theoretical, which were made in front of “Jigger”, which he agreed was in no need of it; and his earlier comment about “Dark Deeds” having “too much three-dimensionality”, and about which I think he has a strong argument to make.

Can you have too much three-dimensionality? I don’t think you can, so long as it is not literal three-dimensionality. In the case of “Dark Deeds”, I think he has a point. MY point – the reason this group of work focussed on these clusters, was to try to get at how to put these assemblages of complex and diverse parts together in such a way that all parts are properly, spatially, physically, “in relation”. In other words, nothing is to be left in isolation. Did I go too far down this road? Certainly, but it did work for at least two of the works (I think it works for “Orangetree too, but that didn’t get looked at). I think there is a pay-off when you get it right and the overt physicality of the stuff of the parts (as Tony implies) is in balance with the sculpture’s spatiality.

This business of things “in relation” is something I have just written about on comments on Harry’s work, and I think it is a strong point. The analogy here is that the three-dimensionality of “Dark Deeds” is literal, and the space in it is “geographical” or “positional”, rather than expressive. Mark saw in it parts that he felt could be MORE three-dimensional, were they to be freed from other stuff making up the numbers, so to speak, of the cluster. Yes, I agree. The point is to make the three-dimensionality expressive and coherent and spatial, and as open as possible to sight, whilst retaining that close-quarter relationality. If the three-dimensionality is merely geographic or positional – or dare I say compositional or configurational? – then it fails.

As we will see as we go through the next few Brancasters, opening out into space can be just as problematic…

LikeLike

And I forgot to say that for things to be “in relation”, they HAVE to be moving in relation…

Be nice to have some other voices on this!

LikeLike

Just to TRY to be clear about some things.

When I was talking about seeing what you’re looking at, I was trying to get at the importance (for me) of Noella’s and Alex’s exchange at the beginning of the Brancaster—their exchange about the hanging pieces and the pieces on the floor. Noella was kind of relaxed about the “differences.” Alex felt the “differences” were very important. (And Robin agreed with both of them.)

The exchange helped me get past focusing on the hanging of the hanging pieces. It allowed me to see the hanging pieces as simply different from the pieces on the floor—and to start thinking simply about that difference. For me for a long time sculpture on the floor has been a “bad idea”—an English thing, something else Caro was horribly wrong about. It’s been especially delightful (for me) to see Tony’s recent work (in Brancasters) up on pedestals—up off the floor—and, as I recall, without anybody saying “boo.” I’m “happy” with Robin’s hanging pieces for the same “reason.” They become more accessible—not really literally easier to see—but the “world of illusion” they live in isn’t disturbed by the monstrous/“real” floor.

Thinking about the photographs in this context gets tricky. Photos of the hanging pieces can seem flat. The floor kind of gives more depth to the pieces on the floor—but I’m afraid that depth is “literal.” Robin’s photographs are kind of frighteningly/intimidatingly “good”—but I’m not sure this “goodness” helps. In many ways it was very hard to see the work in the film/video/whatever of this Brancaster. There were so many pieces that different pieces kind of ran into each other. Not all the pieces were “covered.” Still, I felt closer to the work in the film.

One of the things I’m learning bouncing between this Brancaster and the Giacometti show is that there almost aren’t any “surfaces” in a Giacometti—at least, not in his “late” figures and heads—certainly no homogeneous surfaces. I’m seeing the Giacomettis as VERY close to Robin’s sculptures—more densely packed, but agglomerations of “lumps”/3-d parts—and such a startling variety of “lumps”! And, of course, Giacometti is always “opening out.” Space doesn’t have a “surrounding role.” Space AND form are not “geographical”/“positional”/“compositional”/“configurational.” Expression (NOT “Expressionism”) is always the driving force. But he’s not going down a “road,” not trying to balance the overt physicality of stuff with spatiality: that just results in a kind of deadly evenness. He’s looking at his wife for the ten thousandth time. She’s in a bad mood. He’s in a bad mood. And then he sees something. He’s trying to be true to what he sees.

LikeLike

Jock, I actually felt that there weren’t the huge differences between the hanging pieces and the floor pieces this year, as there were last year. Hope I haven’t misunderstood you. There didn’t seem to be such a gravitational pull. I suppose I wasn’t reading them in relation to the floor in the same way as last year. The sculptures this year felt ‘lighter’ visually.

LikeLike

Yes, Noella, that was the “message” I got from what you said. Relax about the differences. The vitality of Robin’s plastic consciousness is enough to separate his sculptures from the “real” world—even from the floor—but it’s the fact of separation, not the actual distance from the floor, that matters most.

And as they separate themselves from the “real” world, they become more accessible. Such a tricky business. Where does a Giacometti bust “begin”? Is that mountainous mass including and below the shoulders part of the “sculpture”—or just part of the “base”?

And thank you–and all the others–for participating in these chronicles. You all help me “see” the work here in New York. Maybe it’s a crazy way to look at the work, but it sure is better than nothing.

LikeLike

Would that I could say “Our pleasure”, but Brancaster is not here to help you “see” Giacometti (though if it could, you might realise his limitations). We are here to try and progress ideas about abstract art, which you don’t even think exists, so perhaps you should bow out. If you do continue to contribute, maybe you could think a bit harder about something other than your own subjective fixations. It would also be polite to spell Noela’s name correctly.

So far, so poor on these sculptures. Let’s have some more and different opinions, because the discussion has not opened out at all. I do believe, though I say so myself, that the sculpture is worth it.

LikeLike

Morning Robin

On balance I do not share your irritation with the comments from Jock ….on the contrary I more often than not welcome his efforts,as a figurative artist, to express his opinion about what we are discussing on this our Brancaster Chronicle site.

“So far ,so poor on these sculptures”……???

Whilst you have been having getting into a bad mood this is were I have got to…..

I do not remember there being a serious debate about relational and non relational sculpture to date. Chronicles no.1 and no.2 opened with non relational work.

What I am wondering is whether the sculptures under discussion here today are representative of both and how the issues of sculptures’ physicality, space and three dimensionality change as a result.

Over on Harry’s discussion the debate continues on this very dual subject or has Harry or his audience begun to see his two paintings as sitting in the middle of both.

Is this a subject for debate in sculpture now?

LikeLike

Maybe, but perhaps you need to say what you mean by non-relational. I have made a clear distinction on Harry’s BC between work where all parts are “in relation” and the idea of a kind of “Greenbergian” relationalism, wherein the separate parts are optically winking away at you from their geographical positioning. Beyond that distinction, I don’t understand “non-relational” very clearly, other than as a kind of minimalism. Care to explain?

LikeLike

“What is the difference ?” is a better question for me and put simply one of them tries not to be relational.

I can’t avoid feeling that it is ‘things’ that are ‘in relation’.

But the bigger reason for my enthusiasm for non relational is that it seems to work better for ‘all the balls in the air’.

It might be said that relational and its association with ‘things’ puts a limit on the range of influence of any of the ‘balls’.

‘Things’ have qualities which repeat features of themselves as ‘things’ [ like tops,sides,bottoms,inners and outers etc.] If one were seeking variety, with relational, you would clog up the ‘thing’ very quickly with repeats. [perhaps this has something to do with Mark’s comment on too much three dimensionality?]

You raising minimalism comes in here at this point where repetition , natural to objects and ‘things’, would fill up the space with many repetitious three dimensionalities.

What I am suggesting might help give more space in the sculpture for a real complexity of all the balls.

LikeLike

So if you take out all the things and all the relationships, what do you have? Balls?

I can’t imagine any art that is any good not having every”thing” in relation. “Thing” is only a shorthand for whatever content you are dealing with, and could in fact itself be a relationship or set of relationships (of course, you don’t like the word “content”, because it flags up “things”, but it could just as easily mean the activity of relationships across the work). We have spoken in the past about parts, and how, when everything starts to works together, one need no longer talk about parts… and I agree, but in that case, what does “work together” mean other than everything being in relation?

If I understand your terminology correctly, the “balls” are attributes like three-dimensionality, spatiality, etc., that a sculpture may or may not deal with, and perhaps the more it gets on board the better. But if you lose relationships, you are in a kind of indeterminate and vague minimalist territory that maybe is good for you, but not for me. No thanks. However, I don’t think your work inhabits that territory either.

I can’t say I think the following is a true statement anyway, but I’m hoping you don’t think “repetition, natural to objects and ‘things’, would fill up the space with many repetitious three dimensionalities” applies to my work – but if so, let’s have it.

LikeLike

Here’s an idea to try to keep this going forward.

Why don’t you tell everybody more about your comment ‘for things to be in relation they HAVE to be moving in relation’

To me that is interesting and wonder where it originates.

Regarding what I may think “work together” means, I would say everything knowing of everything else.

For me that would be the key to non relational because in relational , things may be winking at each other across the floor but that does not mean they know each other !

My answer to your last paragraph is simple, I do not need to refer to your work I have 50 years of that shit of my own .

LikeLike

I think we are arguing over words. If things/people/whatever “know each other”, they are in a relationship! Like we are! I ain’t winking at you.

I’ll think on the “moving” thing. Meantime, what would really move this forward would be some other opinions.

LikeLike

OK, ‘for things to be in relation they HAVE to be moving in relation’ – by which I mean that relationships are dynamic or, if not, then they are nothing, just juxtapositions. One might have cited collage as an example of static juxtaposed elements, were it not for the fact that Mr’ Bunker has demonstrated that collage can also have dynamic relationships and movement.

I use the term dynamic in the sense of being “characterized by constant change, activity, or progress”.

LikeLike

I wasn’t there, so I’ve only got the photos to go on, and I’m no sculptor so this is very much a lay opinion, but I’m surprised no one has mentioned how amazing “orangetree” looks from the angle illustrated.

It feels so natural, so perfectly balanced, and it seems completely alive and happy on its support – not slumping like “Ganix Weyn”, not overly stiff and heavy like “Shot Thro” nor impossibly pert like “Dark Deeds”, nor threatening to hinge open in the middle like “Estomac” (all just subjective and exaggeratedly negative impressions of the single views).

I know this is pictorial thinking, but I wonder whether it might have some relevance.

(And no, not an engine block in sight!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jigger and “Dérangement d’Estomac” stood out for me on the day. Both are complex works, Jigger being a denser work where the narrow thin bars create an interesting and dynamic relationship with the bigger flat pieces. There is great placement of such diverse elements. “Dérangement d’Estomac” is less complex in terms of material but the space (negative space?) opened up between the metal compliments the material, becoming a complex element itself. One interesting thing for me is that when I was looking at them the hanging bar, in the case of “Dérangement d’Estomac”, and the floor, in Jigger, disappeared. I take this as a positive thing, that the sculpture itself dominated the space in a positive way. This may be similar to a successful painting when the materiality of the paint disappears or is transcended, or when there are no specific areas that fail in relation to the rest of the painting.

Mark wondered whether this abstract three dimensionality is ‘as far as you can go’, ‘where do you go from here?’ It’s a good question but these two sculptures do open up two distinct ways to explore, even though they both share a complex diversity.

To clarify on these two ways, which diverge due to their focus or emphasis (with the caveat that both share complexity):

1. More complex and diverse material with less negative space (material dominates)

2. More complex and diverse use of both material and negative space (more balance between material and negative space)

Questioning this a third option of ‘negative space dominating’ arises. But this would perhaps result in a simpler and less interesting sculpture (?).

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the things I find so striking about this body of work is just how very different it is from the one Robin put together for his chronicle last year. It has been mentioned that these sculptures don’t have such clearly distinguishable identities. There aren’t the orbiting satellites of “Grand Rubica”, or the dramatic toppling poise of “Yellow Rattle”, or the vertical surge emanating from the space below “UPressure” (though that may be happening to some extent in “Ganix Weyn”). Yet I get the sense that this year’s sculptures start to establish a slower sort of identity for themselves as they are looked at over time.

It is also worth noting how there is much less of a comparison being drawn between the use of wood and steel together. Last year there seemed to be a more even distribution of both materials. This year it is mostly steel, but where other materials have been used, they seem to sit quite happily within the whole structure, quietly but assuredly going about their business.

I like what Richard says about that view of “Orangetree”. It’s like it has just fallen into place, yet not in a way that looks at all random. That section of wood plays such a crucial part in opening up the movement through the piece, but without drawing much attention to its literal materiality.

There has been a bit of talk about structure, here and on my chronicle. I’m sure it will come up again in the ones that follow. I think structure is something to aim for, but in a way where it is not so easy to see where the artist has tried to achieve it. Put simply, Robin is seeking NEW Structure, and in that view of “Orangetree”, and perhaps many more, he looks to be getting at it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks to Richard, John and Harry for those comments, and in particular for trying (in the case of R. and H.) to make sense of the work from photos. I’m interested by the focus on “Orangetree”, which as I mentioned earlier I regard as one of the more successful pieces. Of course it may be just this particular view that is being responded to… which brings me to the first point I want to unpick.

Some time ago, when I posted a photo of a sculpture on Twitter, John suggested that it would be much better if I posted a set of photos taken around the work from different views – a sort of north, south, east and west set of shots – in order to give a better idea of the work and allow people to work out better the structure of the sculpture. This seemed eminently sensible, and it was something I had automatically done many times myself in the past, including to some extent in previous Brancaster posts. But I now found myself thinking not only that this was not always the best way to illustrate even simple sculptures, since you have to pick your views very carefully indeed in order to NOT give impressions of things connecting in certain ways that are false – assumptions that would be disabused in real life by even the slightest movement of the head – but also that in the case of these newer, more complex sculptures, there is no longer quite the same kind of structure(s) operating in the work that would be made accessible by such a set of photos.

Taking things further, there are two aspects to this. Firstly, in this set of sculptures I have worked quite consciously, rightly or wrongly, on trying to eliminate the linear structures of literal, stand-up sculpture that makes its content out of a response to gravity. I know this is somewhat contentious, but I’m pleased to see, for example, John’s comment about being unawares of either the floor or the hanging rod when looking at “Jigger” and “Dérangement d’Estomac” respectively, and Richard’s comment on how “Orangetree” is natural and unlaboured in its hanging. My original interest in hanging the sculpture, and also in the inclusion of different materials, such as the wood, but also stones and plastic, was to deliberately disrupt the reading of the work as physically literal organisations, and to make the eye of the viewer move in different ways from how steel construction is often read. But I now see both these strategies as problematic in their own right, and what little is left of the wood etc. in these newer works (compared to last year) has been more a case of recycled content rather than deliberate insertion. Indeed, I now think that the inserts of wood and stone in works like “Shot Thro’” are in some ways analogous to the “relational” and optical bits of “winking-at-you” material, geographically arrayed, that we have been discussing here and on Harry’s BC as being problematic. I think it works slightly differently in three-dimensions, but nevertheless I feel I’m rather done with this as a means to break down my own presumptions about structure. And as Harry optimistically implies, I hope I am getting into a different sort of more sculptural structure in the best of this set of work without such devices.

The second aspect is to do with the continuity of experience of content in the work. This is essentially to do with three-dimensionality and moving round a sculpture, and how the experience of the work links together as a coherent whole, outside of, or separate from, the literal space of the room, from however you approach it. This experience would not be served by a thousand photographs, nor reproduced by a video. The reason I rate “Orangetree” is because it keeps at bay the literal space of the room by continually, and in a sort of “staccato” motion, shunting the space it takes as its own onwards by degrees, through and back through itself, in an endless set of dynamic relationships. This is what I meant by a balance between overt physicality and spatiality, which Jock was so keen to disparage as a kind of “deadly evenness”. It seems alive to me, because it’s forever in the balance, not fixed.

So the continuity is not linear, nor is it geographic or positional. That, at least, is my hope, because it is upon the continuity of these new kinds of structures that I put my faith with regards to the wholeness of the work. My ambition is for all the content to be “in relation”, or have a kind of “self-knowledge”, to paraphrase Tony’s preferred terminology. I’m not very interested in thinking much about the differences between the material and the space in the work, and whether space is to be thought of as another material etc. I think they are, or should be, bound together as indivisible content. I’m very relaxed about the hanging thing, the different-materials thing, the standing-on-the-floor thing, the cluster-or-not-cluster thing, even – now – the three-dimensionality thing, because a different way of structuring the work and how I think about it is emergent.

LikeLike

Blimey, that shut you all up! Here’s my self-criticism – too much brute force, not enough illusion. I need to believe even more in the subtle power of the content to get through to what is abstract. I’m going on a (semi) vegan diet in both life and art.

LikeLike

Everyone’s died, right?

LikeLike

Not dead, just savouring the semi vegan subtleties.

It appears to me that the work is benefitting from a kind of relaxed attitude to a number of issues, be it gravity, materiality, suspension, space as material etc. You’re not getting too hung up, if you’ll pardon the pun. I can remember John Bunker in the Greenwich chronicle talking about the edges of his collages, and how they had become a more vital element within the work, almost as a result of not worrying too much about them.

I can see a parallel here, with the way the wood in “Orangetree” has come about via a kind of recycling method. Also, the decisions as to whether the sculptures are suspended or left on the floor seems to come from an entirely inquisitive approach that is not at all precious or clinging to an idea as to how the thing ought to work.

It must be a very exciting place for you to be in, Robin. A place where the possibilities seem to open up the more you sift through these problems and potential solutions. Impressive too that the work should remain so focused amidst all this ‘freedom’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well thanks Harry, and glad to know you haven’t perished in the general silence. You paint a very rosy picture, but I still feel very much like there is a long way to go and new problems to overcome. I doubt this will ever change, abstract art being a thing that is forever redefined by all our efforts. I’ve already reworked a few of these sculptures (saving the best, I hope), but even the ” recycling of content” thing is up for questioning, I think, since I need to move on into something a bit different in order to come at the “new structure” from a different and new direction. And there is definitely an issue with the repetition of the “cluster”, which Mark pointed out a long time ago can become yet another configuration. I still think, though, that the way for me to work through all this is via yet more focus on developing the content…

LikeLike

It is a rosy picture, and possibly not so helpful when it comes to moving forward. But from where I’m sitting, it is hard to pick these works apart, and so I can only agree that their impact will (hopefully) continue to be redefined by the work that succeeds them. I think that it is very clear that huge steps have been taken since last year. Perhaps the next stage will prove even more challenging, as the issues become more and more concentrated, and less to do with general problems such as suspension or integration of different materials.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Apropos Robin’s recent (ish) essay on the impossibility of submitting non-conceptual, abstract sculpture for competitions/commissions such as the fourth plinth, I wonder if some of these couldn’t be reimagined as maquettes for something much larger. “Jigger” looks like it would be stupendous (seriously), not on the plinth but as a huge replacement for Nelson’s Column or the Orbit thing.

“Baroque Pastorale” looks like it might work in fourth plinth size; “Sailor’s Trousers” and “Norse Laws” less so.

Could this also mean that “Jigger” is too small for its wealth of content? Is it architecture? Or is it just the one view in the photo?

LikeLike

No thanks, Richard. You have a very fertile imagination. I hope you will come and see the work – see what you think then.

LikeLike

Coming into the room of these nine sculptures and looking, thinking and talking about them for an hour and a half or so, and trying to get some clarity on what they are, and are not, doing and how succesful they are, is pretty difficult, for me anyway. Focusing on three for most of the discussion makes sense but one is left wondering not only how our opinions might change on these three if we spent another hour on them, but on what we might have overlooked. But this is what you get with ambitious, complex non-patterned art works. There is an argument for showing less work in a chronicle (see Harry’s and Mark’s successful chronicles with two or three works), although I am not advocating this.

LikeLike

Simple solution – if its an issue for you or anyone else, give the work some time prior to the Brancaster Chronicle discussion starting. I do believe the opinion was expressed in the talk that it was good to see such a range of work.

LikeLike

BTW what is a semi vegan diet in art?!

LikeLike

It’s a very flippant remark, is what that is.

LikeLike